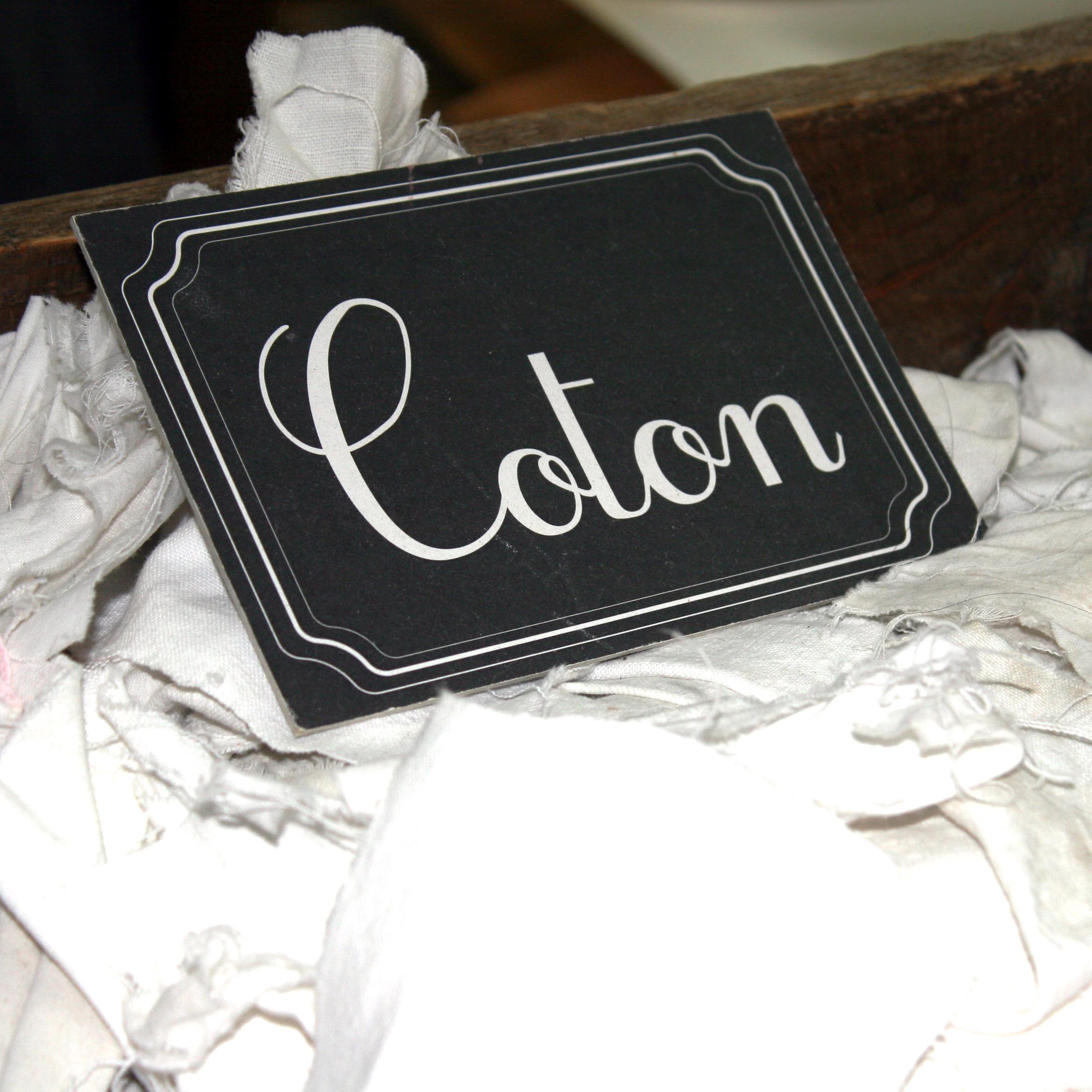

Finally, the pulp is transferred to a copper vat.

It is white, relatively liquid, and maintained homogeneous through brewing. At that stage, one can add flower petals, fern leaves, and many other carefully selected natural products

At this time the paper maker can show his skill.

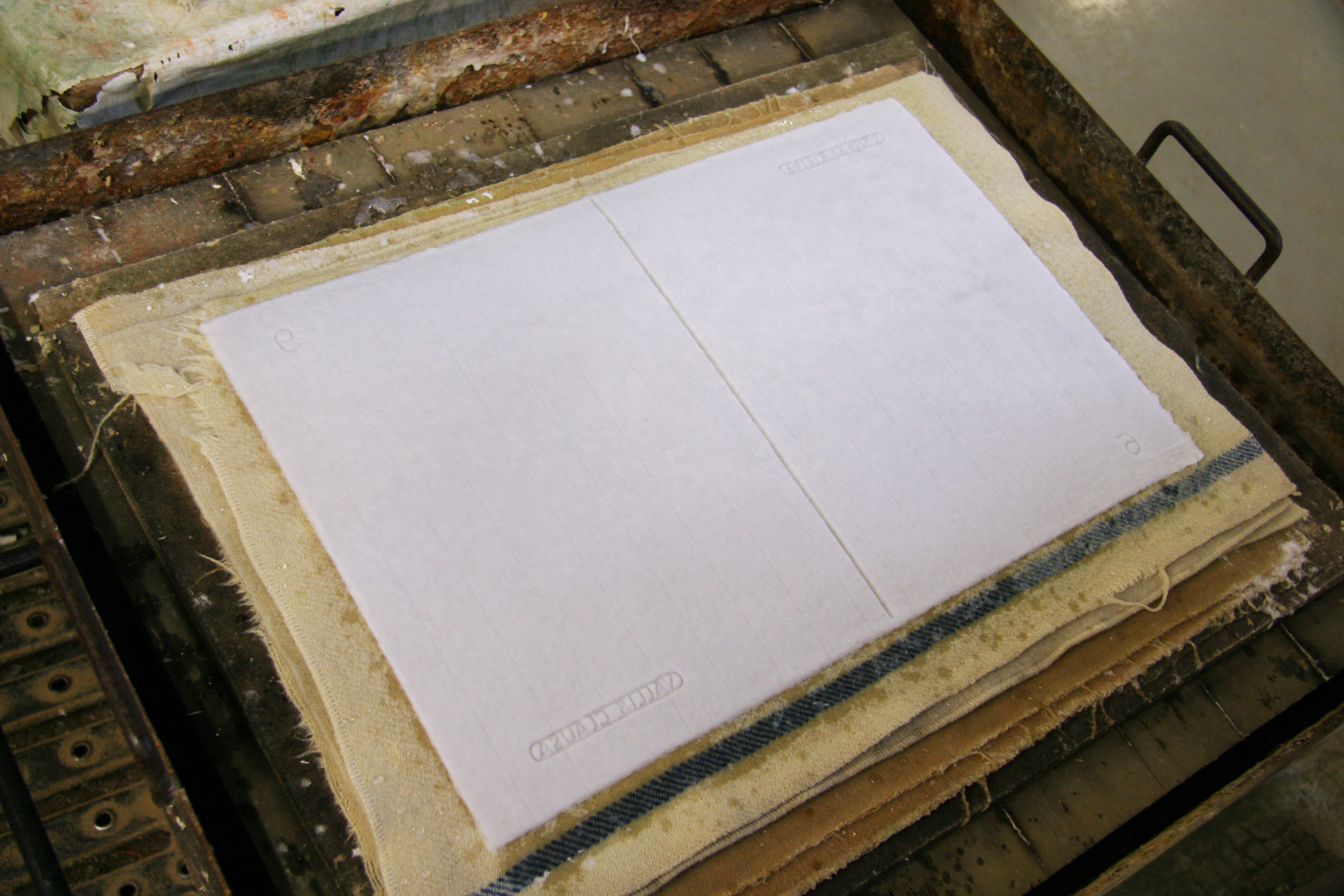

Leaning against the rim of the tank, after mixing the pulp with the”redable”, the papermaker immerses the “Form” (kind of sieve) same size as the future sheet of paper in the liquid.

This form is made up of two parts. First a wooden frame on which is stretched a tight frame of wires supported by wooden rods; this sieve will let the excess of water go through. Then a second frame, the “cover”that fits exactly on the first frame. The cover retains the fluid paste on the sieve and, as a result its height determines the thickness and size of the future sheet. The papermaker sews the watermark, and possibly a slice (brass thread or string) that will allow the sheets to be shared easily when dry.

Cookie preferences

Cookie preferences